Deception Detection Technology: Elle Pearson

First year student Elle Pearson participated in an online poster competition during the Royal Holloway Annual Doctoral Conference on 10 and 11 June. Elle was placed fourth and received an honourable mention for her poster. You can view the poster and the accompanying short essay below.

“I’m fine” is likely the most common lie you hear as people tend to lie the most about how they feel (DePaulo & Kashy, 1998). Lying and deception is too nuanced to claim that it is simply ‘bad’ and shouldn’t be done, it is a complex human trait and behaviour, with children beginning to lie from the age of two (Talwar & Lee, 2008). Of course people lie for nefarious reasons, but people also lie for good-hearted reasons or to protect themselves, either psychologically or from a situational danger (DePaulo, 2004). Some research also points to deception and lying being an evolutionary trait that allows humans to work together cooperatively (McNally & Jackson, 2013).

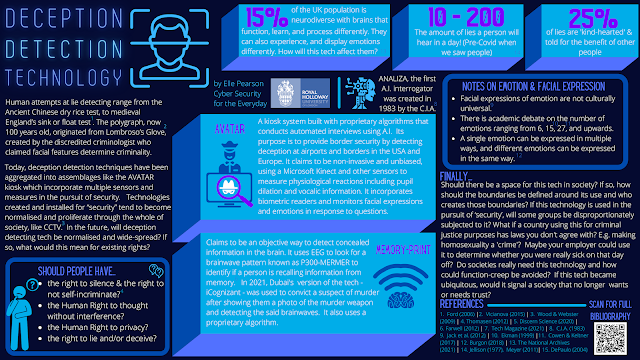

Humans have always tried to identify deception with various methods ranging from the ancient Chinese dry rice test, medieval England’s sink or float test (Ford, 2006), to the polygraph which is now 100 years old (Vicianova, 2015). In 1983, the C.I.A. created ANALIZA, an artificially intelligent interrogator to helpdetect deception (C.I.A., 1983). In the 21st century, digital technology has allowed for an aggregation of different deception theories into digital assemblages that attempt to identify deception by monitoring physiological reactions. The AVATAR kiosk claims to do this using multiple sensors and measures such as heartbeat, pupil dilation, vocal stress indications and also micro-expressions whilst it interviews people (Discern Science, 2020). This tech appears to be a newer version of SPECIES, a similar kiosk (Derrick et al., 2011). The Memory Print claims to use brain waves to identify deception (Farwell, 2012) and is framed as the equivalent to a fingerprint. It claims to use P300 brain waves to identify if someone is retrieving something from memory e.g. that they recognise a murder weapon shown to them.

Two issues with this technology will be addressed in this short essay. The first is… does this technology really work? The second is… if it does work should we use it? The two examples provided use proprietary algorithms making them secret and hidden from peer scrutiny. The tech is based on other areas of research where there is still academic debate occurring. One of these is in the area of emotion and micro-expression recognition where there is ongoing research and debate into how many emotions there are. It began at six, then fifteen, (Ekman, 1999) now it’s at 27 (Cowen & Keltner, 2017), with others claiming there is a lot more across different cultures and languages. This tech reduces humans to a small set of emotions, usually seven, despite the current academic debates.

Despite there being no agreement on how many human emotions there are, this tech assumes that emotions are expressed in the same way across all of humanity. This is not true with research showing that facial expressions of emotion are not culturally universal (Jack et al., 2012). Other research shows how a single emotion can be expressed in multiple ways and different emotions can be expressed in the same way (Burgon, 2018). As well as differences across cultures and languages, there is also differences in age and gender (Abbruzzese et al., 2019).

When it comes to the brain, no brain region is found to correspond consistently with truth-telling or lying (Jenkins et al., 2016). The brains of left handed people, about ten per cent of the population (BBC, 2020), behave differently so they are excluded from any brain scan research (Volz et al., 2015). Fifteen per cent of people are neurodiverse with brains that function, learn and process differently and may also express emotion differently (The National Archives, 2021) . This means that 25% of the population could be immediately misinterpreted by this tech. There is also a methodological flaw in this research such as statistically irrelevant sample sizes to participants being told to lie (Jenkins et al., 2016). How do we know whether the brain areas, or brain waves, are those that deal with deception or with instructions?

The second concern is, if this tech is widely operationalized because it is deemed accurate enough, should it be? What could this mean for existing rights such as how this tech may bypass the right to silence when accused of a crime and the right to not self-incriminate (Thomasen, 2012). It could also interfere with the Human Right to privacy and to thought without interference. It raises questions on being human and whether people should have the right to lie and deceive if they wish to?

The rationalisation that will be provided is terrorism… that we need the tech to stop a terrorist attack. It may begin there but how could function-creep be prevented? Technologies created and installed for “security” tend to become normalised and proliferate through the whole of society and will spread like other technologies rooted in security such as CCTV (Wood & Webster, 2009). Another argument will be, “well if a person has committed a crime then it is ok to use this on them”. But what if you don’t agree with the criminalization of certain activities? What if homosexuality is deemed a crime again? Should it be used then? Imagine a criminal justice system that uses such tech to identify people lying for their own protection, say because of sexuality or religion. Imagine this tech being used by a dictator to identify loyalty. It would also likely be used for benefit claimants, insurance purposes (voice monitoring is already used) and also in employment (emotion recognition and micro-expression is already being used).

Avatar has already been used to secure borders in the USA and Europe, Memory Print has been used in a few US criminal cases and most recently this year it was involved in a murder case in Dubai (Tech Magazine, 2021). Should such technology be rolled out without societal consultation? Would the large scale adoption of this technology signal the real-world manifestation of a trustless environment? If it is decided that the human trait of lying and deception should be eradicated via technology, what other human traits could be deemed undesirable and who gets to decide?

References

Abbruzzese, L., Magnani, N., Robertson, I.H., & Mancuso, M. (2019) Age and Gender Differences in Emotion Recognition. Front. Psychol. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02371/full [Accessed 2 June 2021].

BBC (2020) Amazing facts about lefties for Left Handed Day. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/53739189 [Accessed 2 June 2021].

Burgon, J.K. (2018) Microexpressions are not the best way to catch a liar. Frontiers in Psychology. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01672/full [accessed 2 June 2021].

C.I.A (1983) Interrogation of an Alleged CIA Agent, Declassified Articles in Studies in Intelligence, 27 (Spring) Document No. 00619182. Available from: https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/document/0000619182 [Accessed 2 June 2021].

Cowen, A.S. & Keltner, D. (2017) Self report captures 27 distinct categories of emotion bridged by continuous gradients. PNAS September, 19, 114(38) https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702247114.

DePaulo, B. M. (2004) The many faces of lies in Miller, A.G. (ed) The Social Psychology of Good and Evil. New York: Guildford Press.

DePaulo, B.M & Kashy, D.A. (1998) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74 (1) pp.63-79.

Derrick, D.C., Jenkins, J.L. & Nunamaker Jr, J.F. (2011) Design Principles for Special Purposes, Embodied, Conversational Intelligence with Environmental Sensors (SPECIES), AIS Transactions on Human-Computer Interactions, 3 (2). Available from: https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1028&context=thci [Accessed 3 June 2021].

Discern Science (2020) | Automated interviewing technology reveals deception. Available from: https://www.discernscience.com/avatar/ [accessed 3 June 2021].

Ekman, P. (1999) Basic Emotions in Dalgleish, T. & Power, M.J. (1999) Handbook of Cognition and Emotion. John Wiley and Sons: USA.

Farwell. L.A. (2012) Brain Fingerprinting: a comprehensive tutorial review of detection of concealed information with event-related brain potentials. Cognitive Neurodynamics, 6(2) pp.115-154.

Ford, E.B (2006) Lie detection: Historical, neuropsychiatric and legal dimensions. International Journal of Law and Psychology, 29 (3) pp.159-177.

Jack, R.E, Garrod, O.G.B., Yu, H., Caldara, R. & Schyns, P.G. (2012) Facial expressions of emotion are not culturally universal. PNAS, 109 (19) pp. 7241-7244 Available from: https://www.pnas.org/content/109/19/7241 [Accessed 2 June 2021].

Jellison, J.M. (1977) I’m sorry I didn’t mean to, and other lies we love to tell. Contemporary Books: USA.

Jenkins, A., Zhu, L., Hsu, M. (2016) Cognitive neuroscience of honesty and deception: A signaling framework. Curr Opin Behav Sci, 11 pp.130-137. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5042136/ [Accessed 2 June 2021].

McNally, L. & Jackson, A.L. (2013) Cooperation creates selection for tactical deception. Proc R Soc B 280. Available from: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rspb.2013.0699 [Accessed 2 June 2021].

Talwar, V. & Lee, K. (2008) Little liars: Origins of verbal deception in children. Child Development Perspectives, 7 (2) pp.91-96.

Tech Magazine (2021) Dubai police use futuristic technology to read murder suspect’s mind. Available from: https://techmgzn.com/dubai-police-use-futuristic-technology-to-read-murder-suspects-mind/ [accessed 3 June 2021].

The National Archives (2021) Neurodiversity in the workplace. Available from: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20210104113255/https://archive.acas.org.uk/index.aspx?articleid=6676 [accessed 2 June 2021].

Thomasen, K. (2012) Liar, Liar, Pants on Fire ! Examining the constitutionality of enhanced robo-interrogation. We Robot Conference, April 2012. Available from: http://robots.law.miami.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Thomasen_CONSTITUTIONALITY-OF-ROBOT-INTERROGATION.pdf

Vicianova, M. (2015) Historical Techniques of Lie Detection. European Journal of Psychology, 11(3) pp.522-534.

Volz, K.G, Vogeley, K., Tittgemeyer, M., Yves von Cramon, D. & Sutter, M. (2015) The neural basis of deception in strategic interactions. Frontiers in Behavioural Neuroscience. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00027/full [Accessed 4 June 2021].

Wood, D.M. & Webster, C.W.R. (2009) Living in surveillance societies: The Normalisation of Surveillance in Europe and the threat of a bad example. European Group of Public Administration Annual Conference. Available from https://www.scss.tcd.ie/disciplines/information_systems/egpa/docs/2009/Webster.pdf [Accessed 1 June 2021].

Comments

Post a Comment